The courtroom in London has become the stage for a high-stakes trial that could redefine how tech giants like Apple operate within the digital economy. At the heart of the legal proceedings sits a challenge to the practices of Apple’s App Store, alleging that the company has leveraged its dominance to unfairly extract exorbitant fees from app developers and, by extension, consumers. This case, much like the ones cropping up across the globe, brings forward pressing questions about fairness, competition, and consumer choice in today’s digital marketplaces.

Leading the charge against Apple is a collective lawsuit filed in the UK on behalf of approximately 20 million iPhone and iPad users. The claimants argue that Apple’s monopolistic control over its app ecosystem has allowed the company to enforce a rigid 30% commission on paid apps and in-app purchases. This commission, they claim, has not only inflated costs for consumers but has also stifled creative growth and innovation within the app development community. The suit seeks more than £1.5 billion (.82 billion) in damages, positioning it as one of the most consequential class-action cases in recent tech history.

Apple, however, has not stood idly by. The company argues that not only is the commission rate standard in the industry—with comparable platforms charging similar fees—but that 84% of apps on the App Store are completely free and incur no cost to developers. According to Apple, free apps are often funded by advertisements, meaning that both consumers and developers benefit from access to a robust and secure platform without paying commissions.

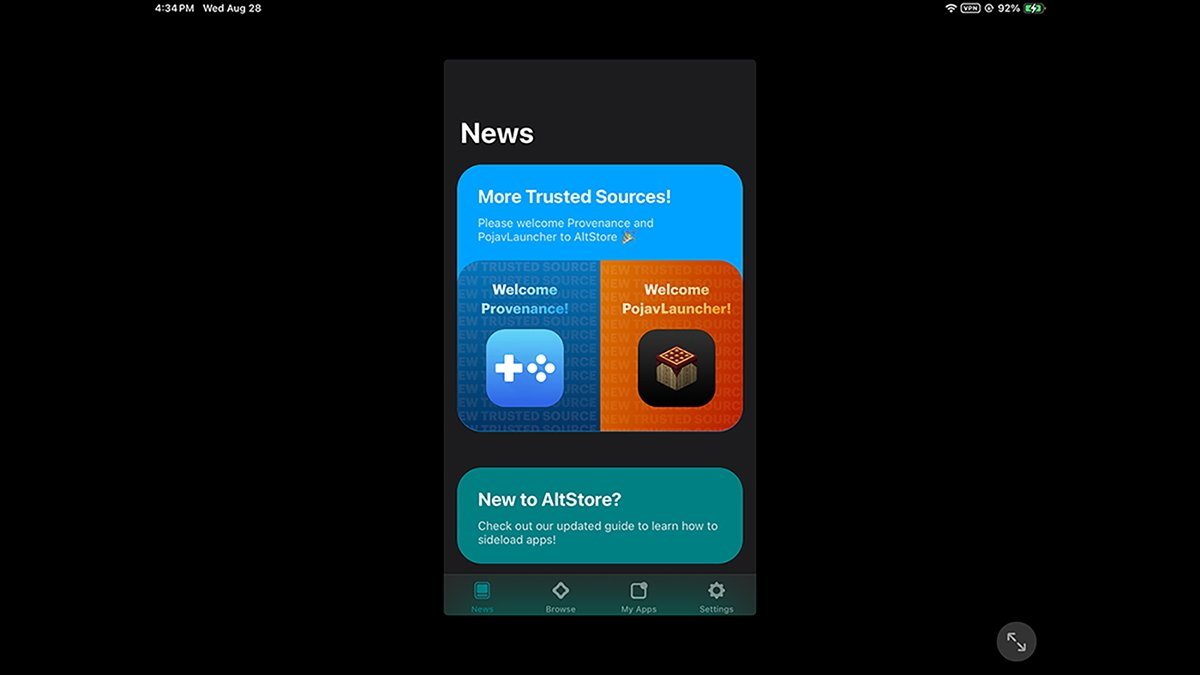

Crucially, the prosecution centers some of its most damning allegations on Apple’s “gatekeeper” role. Since iPhone and iPad users cannot access apps outside the App Store unless they bypass Apple’s software security—an action not sanctioned by the company—claimants have likened this control to an unlawful monopoly. Barrister Michael Armitage, representing the plaintiffs, pointedly noted that the lack of access to alternate app stores has granted Apple what they describe as unchecked power over pricing and distribution. As the claimants frame it, this alleged monopoly handcuffs consumers and leaves them with no viable alternative to Apple’s fee structures.

The case’s implications reach far beyond the courtroom. It represents a key moment in a larger, international reckoning over the practices of Big Tech companies. Regulators and consumer advocates across Europe and the United States have grown increasingly wary of the influence tech giants command and the potential harm such market dominance can cause. Apple’s UK trial certainly shares parallels with ongoing investigations in the EU and legal battles stateside, suggesting a trend that could shape policies affecting app ecosystems globally.

As the trial unfolds, the narrative is raising questions that resonate far outside the legal community. Should digital platforms like the App Store be considered public utilities, regulated for the sake of fairness? Or do companies like Apple retain the right to dictate policies for their proprietary technologies? The answers, while not yet clear, are sure to end up influencing the way we interact with the apps and devices we rely on every day.

The origin of the much-debated 75% profit margin claim adds a layer of intrigue to an already polarizing case. First introduced by the plaintiffs, the figure is drawn from a comprehensive economic analysis undertaken by an independent forensic accountant engaged by the legal team representing the claimants. This analysis, coupled with data shared in parallel cases, such as one brought forth by the U.S. Department of Justice, painted Apple’s App Store as an astonishingly profitable arm of the tech giant’s operations. But how did this specific percentage come to symbolize the alleged exploitative practices of the platform? And how reliable is this calculation amid layers of corporate complexity?

The claim hinges on examining Apple’s financial disclosures, public filings, and expert assessments that attempt to isolate the App Store’s revenues from Apple’s broader ecosystem. At first glance, it’s easy to understand why skeptics might accept the figure at face value: app developers worldwide contribute billions annually via Apple’s revenue-sharing model, with paid apps, subscriptions, and in-app purchases topping the list of income streams. However, the case builds on more than just impressive income figures. It argues that Apple’s operating framework—which combines exclusivity over app distribution with strict policies for developers—creates a situation where these revenues translate into disproportionately high profit margins relative to costs.

The plaintiffs’ forensic accountant reportedly drew from industry averages and competitive benchmarks to arrive at the 75% figure, isolating the App Store’s revenue performance using estimations of direct costs, such as server infrastructure and technical support. These adjustments were made in an attempt to ignore broader costs tied to Apple’s hardware ecosystem (like operating costs for devices). By narrowing the focus, the analysis sought to highlight what they believe exposes a model built on unbalanced profitability rather than shared growth across the ecosystem. Naturally, these findings presented a fertile ground for regulators and critics who have long called for Apple to lower its fees, open its platform to competitive app stores, or justify its policies with greater transparency.

For the claimants, this profitability claim not only underscores Apple’s dominance but builds the narrative of exclusion. To them, Apple’s significant earnings come at an incredible cost to developers who cannot realistically bypass the platform. Alternative models—such as app distribution on Android, which allows downloads through multiple app stores—are cited by the plaintiffs as evidence of healthier ecosystems, though comparisons between Apple and Android app profitability often vary.

However, this claim is far from universally accepted. Critics note the inherent challenges of isolating profitability for a single part of Apple’s vast and interconnected business. For one, the App Store operates as part of a carefully intertwined ecosystem that includes devices, software, and supplementary services like Apple Music and iCloud. Apple’s insistence that costs for maintaining privacy protections, security updates, and developer tools often spill across its products adds complexity to calculations like those leading to the 75% figure. While the plaintiffs treat profitability as an isolated measure, Apple views it as tied to expenses and investments spread across the entirety of their offerings.

What muddies the waters further is the data—or lack thereof—from Apple itself. While the company’s CFO, Luca Maestri, has categorically denied the 75% claim, neither he nor Apple has yet provided precise alternative figures to counter the allegation. Insiders suggest this stems from the inherent difficulty in teasing apart earnings from tightly integrated practices. Apple’s business model relies heavily on leveraging the App Store as a value driver for its hardware ecosystem, making hard numbers elusive when analysts attempt to peel away individual layers of profitability.

As courtroom arguments unfold, the figure has become less a definite number and more a symbolic flashpoint for larger ideological battles. To app developers disillusioned by Apple’s pricing policies, it represents a call to action to challenge dominance in their industry. To defenders of Apple’s business practices, it’s an oversimplified figure used to discredit a more nuanced reality. Either way, the 75% profit margin claim ensures this trial remains an electrifying saga with implications broader than any single company or technology.

As the trial progressed, Apple’s Chief Financial Officer, Luca Maestri, took the stand to address the claim that the App Store operates at a 75% profit margin—a figure cited by the prosecution to bolster allegations of excessive profit-taking and monopolistic conduct. Maestri’s testimony aimed to dismantle this narrative with a detailed breakdown of costs, priorities, and Apple’s wider ecosystem. For a company that has long been at the forefront of consumer technology, the CFO’s remarks provided a rare glimpse behind the curtain of its most profitable digital venture.

Faced with the claimants’ forensic analysis, Maestri outright rejected the 75% profit margin figure, deeming it “fundamentally flawed.” He contended that attempting to isolate the profitability of the App Store from Apple’s highly integrated ecosystem was not only misleading but inherently imprecise. According to Maestri, watchdogs and financial experts often underestimate the operational complexity of running a platform like the App Store, which involves persistent investment in resources that benefit both consumers and developers alike.

One of the key elements of Maestri’s defense was Apple’s significant overhead in maintaining the App Store. He outlined that the costs of infrastructure—such as server farms, high-performance networks, and global data centers—are immense and ongoing. These expenses are compounded by investments in user security, such as encryption technologies, 24/7 fraud monitoring, and routine scrutiny of every app submitted to the store. This multi-layered security system ensures that consumers can trust the apps they download, something Maestri positioned as a cornerstone of Apple’s value proposition.

Beyond infrastructure costs, Maestri highlighted the additional financial commitment Apple has made to support its app developers. Programs such as Apple’s Small Business Program, which slashes commission rates for developers earning less than million annually, were presented as evidence of a deliberate effort to strengthen the app economy beyond just its top-tier players. He also pointed to Apple’s provision of APIs and developer tools, as well as their technical support teams and marketing resources, as critical—and often underestimated—components of the costs that erode any simplified profit percentages.

“The narrative that the App Store is a cash cow ignores the reality of running a secure, global platform at this scale,” Maestri testified. “It’s not a simple percentage of revenue minus a few costs, as our critics suggest. There are indirect costs—such as research, development, and compliance—that are essential both to the App Store and to the broader Apple ecosystem.”

Perhaps most significantly, Maestri contended that the App Store cannot be extricated from the rest of Apple’s financial structure as neatly as plaintiffs allege. Apple’s business model hinges on a seamless ecosystem of devices, software, and services that create a unified consumer experience. He suggested that any attempt to calculate the App Store profits in isolation from the greater ecosystem—where the app marketplace serves to make Apple’s devices more attractive and valuable—would inevitably rely on what he called “judgment-heavy estimations” of cost allocations.

When Barrister Michael Armitage, representing the plaintiffs, questioned why Apple had not submitted alternative profit figures to counter the 75% claim, Maestri was candid. He explained that computing an exact profit margin was virtually impossible due to the aggregation of shared costs and investments. “To claim any specific percentage,” he said, “would require assumptions so subjective that it would further cloud the debate rather than clarify it.” Analysts, he argued, were attempting to distill a nuanced business model into over-simplified financial metrics.

Maestri’s testimony also pushed back against the idea that the 30% commission rate on app transactions or in-app purchases was inherently discriminatory or unfair. He pointed to the industry-wide adoption of similar commission rates across competing app stores and emphasized that Apple’s fees fund not only operations but also continuous innovation. When asked whether the App Store’s revenue could sustain lower fees, Maestri warned of potential downsides: a reduced profit margin could translate to diminished investment in security, tools, and systems that developers and consumers alike depend on.

To drive home Apple’s counter-argument, Maestri echoed one of the company’s long-standing defenses: consumer and developer trust. “Developers can feel confident that their apps are showcased on a platform specifically curated for quality and safety,” he said, pausing to underline examples of Apple’s crackdown on malicious apps. “And consumers know they get what they pay for. Apple’s standards ensure that trust, and trust isn’t free to maintain.”

For all the clarity Maestri hoped to bring to the discussion, his testimony did raise more questions about Apple’s reluctance to release precise financial breakdowns for the App Store. While he asserted that any such calculation would be speculative, the absence of hard data left critics unconvinced and arguably played into the perception that Apple remains opaque in its financial reporting in this regard. With the onus placed back on the plaintiffs to substantiate their claim, the court’s next steps would dive deeper into the heart of this financial and philosophical divide.

For now, Maestri’s rebuttal serves as a reminder that the controversy surrounding the App Store reflects broader debates gripping the tech industry. Is Apple an innovative trailblazer, investing in the infrastructure and resources that support millions of developers and billions of app downloads globally? Or is it an entrenched gatekeeper, leveraging its ecosystem dominance to extract disproportionate profits from an ecosystem it polices with little external oversight? Only time—and a court ruling—will tell.

The reverberations of the trial extend well beyond Apple’s courtroom battles, raising critical questions about the future of app stores and global tech regulation. This moment stands at the intersection of legal, economic, and consumer rights debates, with potential consequences that could reshape the digital landscape for users, developers, and platform providers alike. To better understand the stakes, it’s important to consider the larger forces at play and what this trial symbolizes for the tech industry at large.

Perhaps the most immediate implication of the case is what it could mean for app developers. For years, many developers—especially smaller, independent creators—have voiced frustrations about the control exercised by platform owners, like Apple, over their creations. To these developers, the 30% commission feels less like compensation for a service and more like a toll imposed for simply existing within the parameters of a closed ecosystem. Moreover, critics argue that the lack of alternatives forces them into a “take it or leave it” dilemma, where the rules always favor the host platform. A ruling against Apple could lead to sweeping policy changes, potentially leveling the playing field in a way that empowers smaller studios, innovators, and startups.

For consumers, the trial touches a chord that resonates with anyone who’s ever begrudgingly paid for an in-app subscription or wondered why an app download comes with extra costs. While Apple asserts that its approach maintains a secure and curated marketplace, the plaintiffs argue that consumers are being denied the benefits of competition. Without alternative app stores or payment systems, consumers are funneled into a tightly controlled environment dictated by Apple’s terms. A legal shakeup that mandates broader competition might encourage more choices, improve innovation, and even lead to lower costs for users—though skeptics also caution about potential trade-offs in security and quality assurance without Apple’s oversight.

At an industry-wide level, however, the implications ripple outward in unexpected ways. Other companies and platforms are watching this trial closely, particularly those with similar business models, like Google Play. If Apple’s policies are deemed monopolistic under UK law, it could inspire lawsuits and regulatory challenges not just in Europe but globally. Companies like Google, Amazon, and even Microsoft may feel the strain of increased scrutiny about their own ecosystems, sparking a domino effect of investigations and litigation aimed at unearthing anti-competitive practices across the industry. This could further embolden governments to introduce new regulations that redefine how digital marketplaces operate, from pricing structures to data interoperability.

These shifts wouldn’t arrive in a vacuum. The world is already witnessing greater regulatory momentum, particularly in Europe and the United States. The European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), for instance, has laid groundwork for imposing stricter rules on gatekeepers to encourage openness and competition. The UK trial shares clear parallels with these efforts, and a ruling in favor of the claimants would likely amplify calls for similar legislation elsewhere. In the United States, where Apple already faces antitrust investigations, the outcome of this case could serve as leverage for regulators spearheading such battles.

Still, there remains significant disagreement over how far governments should intervene in tech platforms. While some see this as a vital moment to rebalance power between tech giants, developers, and consumers, others worry about unintended consequences. Apple and its advocates warn that heavy-handed regulation could compromise security, diminish user experience, and disrupt the economic flow that has fueled robust app marketplaces. If platforms face mounting legal obligations—or lose the ability to protect their carefully curated ecosystems—it could ironically make these ecosystems less attractive for both developers and users.

On the flip side, proponents of tighter oversight argue that regulation is necessary to ensure that tech companies align with broader public interests rather than singular profit goals. The echoes of this trial will likely resonate through years of policymaking and industry evolution, offering rare opportunities to untangle the complexities of digital markets and recalibrate rules for a new era of tech.

And then there’s the global picture. The concerns raised in the UK court mirror debates in many other jurisdictions but with slightly different stakes. In regions like India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America—where app ecosystems are already constrained by affordability and infrastructure challenges—the de facto monopolization of app distribution can lead to even greater inequities. Rulings that challenge the status quo could provide an opening for alternative platforms tailored to regional needs, introducing dynamic shifts in what has long been an Apple- and Google-dominated sphere.

What emerges most clearly from this trial is that the digital economy sits in a pivotal moment. Amidst calls for decentralization, developer empowerment, and consumer fairness, the relationship between tech companies and regulators is on the cusp of transformation. Apple’s defense hinges on its ability to convince the court that its practices uphold innovation, safeguard users, and maintain ecosystem integrity, all while challenging critics who claim otherwise. Yet, beyond the letters of law or the courtroom drama, the questions being raised are far more enduring. Should consumers have greater say in the systems they rely on? Can developers claim fairer terms against the giants controlling their access to audiences? How do we ensure the balance between competition and quality?

The UK trial is one chapter in what’s shaping up to be a global reckoning. And while the stakes seem enormous for Apple, the true legacy of this legal battle may be felt in the years of shifts, regulation, and innovation it inspires across the tech world as a whole.