It’s easy to take for granted how we get our news these days. For many of us, we tap open a familiar app, scroll through curated headlines, and click a few articles that catch our attention. But behind those quick taps are real concerns—especially for major news organizations like the BBC. They’ve stepped forward with a critical message: their voice is being lost amid the noise of digital aggregation, and it matters more than we might realize.

The BBC, one of the most respected public broadcasters in the world, has accused tech giants Apple and Google of underrepresenting its brand when its journalism appears in their news apps. News aggregators like Apple News and Google News serve up content from numerous publishers, but BBC executives say these platforms don’t do enough to highlight who actually created the story. And when the BBC’s logo or name is muted or buried, the risk isn’t just about lost visibility—it’s about erasing a trusted identity that took decades to build.

This isn’t a trivial dispute. It touches on how trust is established in an increasingly fragmented information ecosystem. When a story about a conflict zone, health crisis, or political development appears on an app without a clear source, readers may not realize it’s the BBC behind the careful research, on-the-ground reporting, and editorial integrity. That unseen effort deserves credit—and people have the right to know who is informing their views.

What’s more, this issue taps into something even deeper for the BBC: its relationship with the public. Funded in large part through a TV license paid by UK households, the BBC must continually justify its worth to the very people who support it. Strong branding and clear attribution help the public see where their contributions go. When tech platforms blur those lines, the value exchange between the broadcaster and the public is weakened.

Perhaps you’ve seen this firsthand—reading a headline, appreciating the reporting, and never realizing it came from the BBC. That’s exactly the risk: without transparent branding, the lines between respected journalism and generic content get fuzzier. And in times when misinformation thrives, knowing who to trust has never been more important.

By pushing back on these aggregator practices, the BBC is not just protecting its own recognition—it’s calling attention to a broader issue that affects every reader and every trustworthy publication alike. It’s a reminder that in a world of algorithm-fed newsfeeds, the origin of the story still matters. And we, the readers, deserve to know it.

Trust isn’t just about truth—it’s about transparency. And without clear attribution, even the most accurate reporting can lose its connection to the people it seeks to serve. This is especially true for a public service broadcaster like the BBC, whose funding model hinges on the trust and loyalty of its audience. Every pound from the UK television license fee is not just financial support—it’s a vote of confidence in the BBC’s mission of impartial, rigorous journalism. When that connection between journalist and audience is made invisible by aggregators, it jeopardizes more than just brand identity—it threatens the very public mandate that allows the BBC to function independently.

Imagine being part of the public that funds this institution, believing in a shared vision for thorough, accessible news—and then seeing that effort go uncredited on widely used platforms. It’s not just frustrating; it can feel like your trust and your contribution are being taken for granted. The BBC understands that public support isn’t a given—it’s earned, day after day, with every investigation, every broadcast, every breaking news report. Branding isn’t just a logo—it’s a promise. And without that visible signal, many readers may never realize the news they’re relying on comes from a source that operates without commercial agendas and with deep editorial accountability.

There’s also a larger ripple effect to consider. Diminished brand recognition on aggregator platforms doesn’t only affect perception—it can have real financial impacts. While the BBC primarily relies on public funding, other news organizations that supplement their budgets with advertising revenue are even more vulnerable. Advertisers, after all, allocate budgets to outlets that offer engagement and trusted environments. If branding is suppressed, so too is that advertiser-publisher relationship. For the BBC, this doesn’t translate the same way in pounds and pence, but it does impact how it justifies future expansion, international investment in services like the BBC World Service, and overall public trust.

Your feeling of being in the dark about where your news comes from? That’s real—and intentional design choices by aggregators can unintentionally (or intentionally) obscure your ability to make informed choices about the news you consume. It’s empowering to know not just what you’re reading, but who is bringing that story to light. And it should be easy to see. That’s the heart of the BBC’s concern: a call not just for branding, but for transparency, clarity, and respect for both the creators and the consumers of trustworthy news.

The BBC is advocating not just for its own label to be seen, but for a more honest and responsible approach to how we all engage with news. Because when the source is clear, the signal is stronger. And in these noisy times, we should be able to hear the difference.

To help address the issue at its core, the BBC formally submitted its concerns to the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) as part of an ongoing investigation into the dominance of Apple and Google in the digital news and technology ecosystem. According to the broadcaster, there is a significant imbalance in power when large tech firms essentially become gatekeepers to journalism, deciding how—and even if—publishers are credited for their content. The BBC argues that this kind of market behavior is not just unfair to content creators, but ultimately undermines the public’s access to trustworthy information.

In its detailed submission, the BBC voiced its frustration that aggregated platforms fail to provide adequate visibility of the source behind news stories. It highlighted how, on Apple and Google’s news products, stories may appear stripped of any strong visual cue or identifying branding, such as the BBC logo or clear references to the original context in which the story was reported. Without that, readers might assume the story was generated by the platform itself rather than sourced from a public institution that prides itself on impartial journalism.

To be clear, the BBC isn’t asking for special treatment. What they are calling for is equity—a fair playing field in which all content creators, large or small, receive the recognition they deserve. In its CMA complaint, the broadcaster suggested specific measures, such as requiring aggregators to display publisher logos more prominently, ensure bylines include publisher names, and avoid truncating headlines in ways that obscure attribution. Each of these suggestions aims to rebuild the direct connection between journalist and reader—a connection that algorithms should support, not sever.

The urgency of the BBC’s position also lies in its public service mandate. As a publicly funded organization, it has an extra layer of accountability to British citizens, who pay the TV license fee. This unique aspect is central to the CMA complaint, with the BBC stating that a lack of attribution “undermines the perceived value” of its journalism and, by extension, the funding model that sustains it. When the audience is unaware that the BBC produced the content they’re accessing, the value proposition to UK households becomes blurred, and that’s a real concern for both public accountability and journalistic integrity.

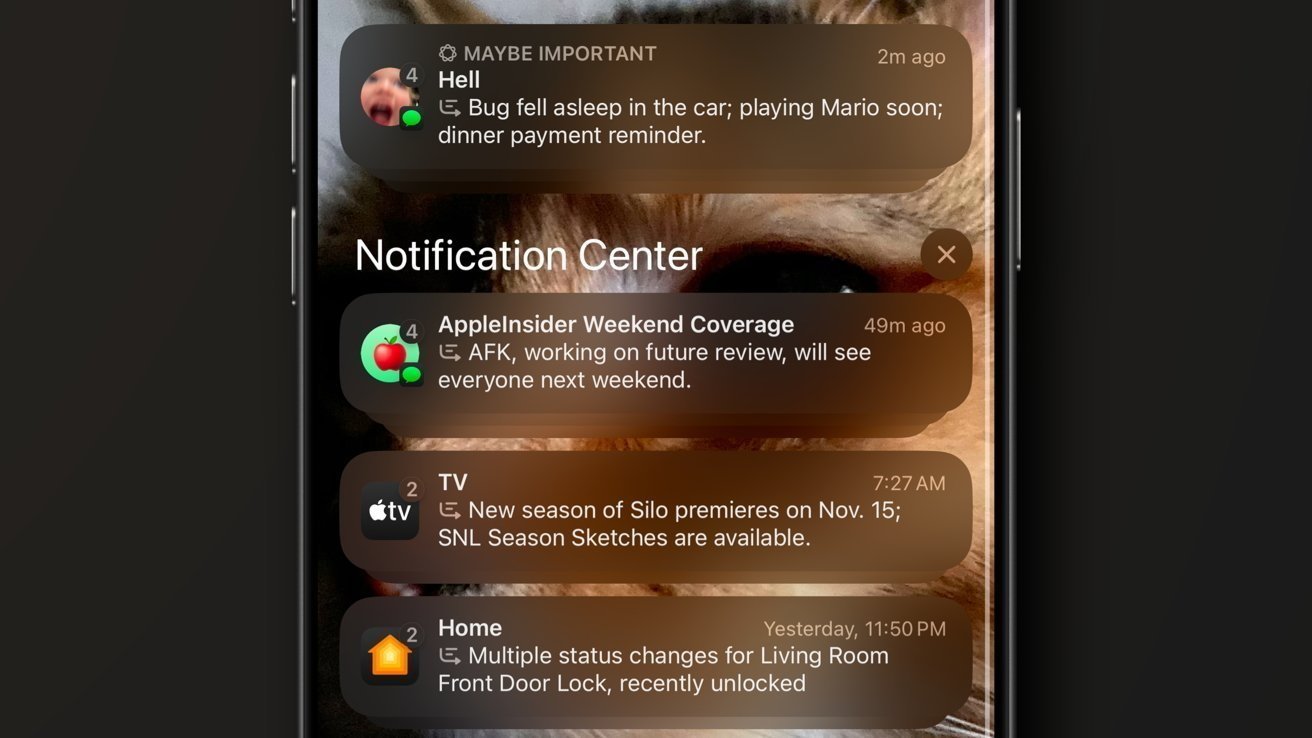

Compounding these concerns is the role that artificial intelligence and summarization algorithms have begun to play on platforms like Apple News. The BBC pointed to troubling examples where its stories were summarized inaccurately or misrepresented by AI tools used by aggregators. While efforts have been made to clarify when summaries are AI-generated, the BBC insists more must be done to protect the original reporting from distortion. In its filing, it accuses these features of misinforming readers and degrading public trust—something that diminishes the BBC’s longstanding credibility, often built on nuanced reporting that cannot be easily captured in a few algorithm-driven sentences.

Furthermore, the BBC raised red flags about how these practices may ripple across the entire media ecosystem. In its complaint, it emphasized that what’s at stake here isn’t just an internal branding concern—it’s a structural challenge that affects all quality journalism. When Apple and Google essentially funnel global traffic through their news apps, the way they curate and credit content has far-reaching impact. If large, trusted institutions like the BBC experience diminished attribution, then smaller outlets, especially local and independent publishers, face an even steeper climb to visibility and sustainability.

It’s worth noting that the Competition and Markets Authority is already deeply involved in reviewing the broader influence of Apple and Google, particularly around market dominance in app distribution and browser technologies. The BBC’s addition to this investigation adds another critical lens: the cultural and democratic implications of branding erosion in digital news. Their submission doesn’t just ask the CMA to investigate—it urges the regulator to implement guidelines that would codify fair branding practices and ensure platforms uphold their responsibility to foster a transparent, trustworthy media environment.

Though this process will take time, it’s a moment that matters. And it’s being shaped not just by legal arguments, but by shared values—truth, transparency, and public service journalism. If you’ve ever felt unsure about who created the news you’re reading, or sensed that trusted voices have been muted online, know that you’re not alone. This complaint is, in many ways, fighting to restore your right to know not just what’s happening, but who is helping you understand it. And in today’s media landscape, that distinction is more important than ever.

In response to these mounting challenges around attribution and visibility, the BBC is taking a proactive, solutions-driven approach—one that recognizes the urgency of the problem without losing sight of what matters most: retaining the public’s trust and upholding the integrity of its journalism. Rather than simply criticize, the BBC is stepping into the arena with actionable proposals. They know they aren’t alone in wrestling with these digital dynamics, and they’re using their influence not just for their own benefit, but potentially to pave the way for all publishers concerned about fair treatment in aggregator spaces.

One of the leading proposals from the BBC is remarkably straightforward: mandatory, prominent brand attribution. This would mean requiring platforms like Apple News and Google News to showcase the publisher’s logo, name, and full byline at the top of each article or story summary. No more hidden footnotes or vague subtext—it’s about restoring the visible connection between reader and reporter, and making it absolutely clear who’s behind the journalism being consumed. For audiences who value truth and transparency, this small change could make a world of difference in how news is verified and trusted.

In addition, the BBC suggests setting universal standards across aggregator platforms for how content is surfaced and labeled. This includes a consistent layout for news previews—where publisher attribution, time of publication, and byline are never removed or minimized due to design constraints. These would be industry-wide improvements, not just fixes for one organization’s woes, because they foster consistency and clarity across the board. If you’ve ever wondered why some stories seem stripped of their identity while others carry it loud and proud, this proposal is about leveling that playing field.

But the BBC isn’t stopping there. They are also looking inward, investing in technology and outreach strategies that allow them to maintain more direct relationships with their audience. This includes promoting their own app and website more intensively, bolstering features that encourage audience loyalty, and improving user experiences so that people feel drawn to view BBC content in its full, branded form. While this might feel like pushing back against the tide, it’s a meaningful way to maintain agency in an ecosystem that often leaves publishers feeling disempowered.

To strengthen these direct pathways, the BBC is also exploring partnerships with other media outlets to build collective influence. There’s growing momentum among publishers—large and small—to form coalitions that advocate for greater fairness in aggregator relationships. If these organizations can present a unified front, they stand a better chance of influencing tech platforms and public policy in favorable ways. Think of it as a digital Union for Transparency: a way for journalism to stand up for itself in the age of seemingly omnipotent tech algorithms.

Part of this larger strategy also involves public education. The BBC knows that even the best policies mean little without informed audiences. Through campaigns and digital literacy initiatives, they aim to help users recognize where their news is coming from and why it matters. It’s about giving power back to the reader—offering tools to discern, identify, and choose the sources they trust intentionally rather than passively consume whatever bubbles to the surface.

There’s also growing interest from regulators, nonprofits, and tech ethicists in working alongside organizations like the BBC to build frameworks for ethical news aggregation. Knowing that future legislation may be influenced by the precautionary steps taken today, the BBC’s proposals are designed not just to solve a single institution’s branding problem, but to help architect a better future for all public-interest journalism on digital platforms.

And here’s the heart of it all: the BBC trusts its audience. They believe that if people see the BBC name, they will know they’re reading work grounded in fact, integrity, and accountability. They just need to make sure that name isn’t hidden from view. Whether through regulatory action, digital innovation, or stronger alliances, the BBC’s strategy is clear—amplify visibility, restore the reader-journalist connection, and defend the right of all citizens to know who is behind their news. And in doing so, perhaps they’ll inspire the kind of systemic change that the digital news ecosystem sorely needs.

These developments could mark a turning point in how governments and regulators approach the digital news landscape. With the BBC’s argument now part of a formal regulatory investigation, the opportunity to shape long-term digital news policy is more tangible than ever before. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) may be primarily focused on competition law and market dominance, but the implications spill over into freedom of information, media trust, and the sustainability of responsible journalism. And while the British regulator’s ruling would be specific to the UK, ripple effects are inevitable. Tech companies often prefer to standardize protocols globally rather than tailor services market by market, meaning any changes inspired by UK regulations could benefit audiences and publishers across the world.

As regulators weigh this moment carefully, one thing is becoming clear: the rules that governed legacy media don’t always apply in today’s fast-evolving tech ecosystem. That’s why many industry experts are calling for a new regulatory framework—one tailored specifically to the realities of digital aggregation. This could include mandatory brand attribution policies, clearer labeling of AI-generated content, and more robust transparency standards for how algorithms rank and present news. The BBC’s complaint may end up contributing to the blueprint of this new era in digital regulation—where journalism isn’t just another form of content, but is protected, valued, and properly credited as a pillar of democracy.

There’s also a growing conversation around duty of care for tech platforms—acknowledging that if companies like Apple and Google act as gateways to public information, they also bear responsibility for ensuring the information is delivered ethically and transparently. This could be embedded in regulation, requiring digital aggregators to treat source attribution with the same importance as data privacy or user safety. For individuals, this means a better ability to discern legitimacy. For news organizations, it’s the chance to regain lost ground, where their voices are not only heard but respected in the way they deserve to be.

Ultimately, supporting a regulatory shift isn’t about penalizing platforms—it’s about raising the standard together. Industry-wide clarity on branding attribution is not just a win for legacy organizations like the BBC; it’s a safeguard for local, independent, and community news outlets that struggle for visibility. When clear attribution becomes the norm—not the exception—it creates a healthier environment for media pluralism, where trust can be rebuilt, and audiences are empowered to actively engage with the sources they choose to follow.

As this issue moves further into regulatory territory, it’s helpful to remember that the future of digital news is still being written. Moments like these invite us all—readers, journalists, tech leaders, and policymakers—to reimagine how we meet the public’s right to quality information. Whether through UK-led initiatives or broader global coalitions, the pursuit of fair and transparent news regulation sends an important message: journalism matters, and the integrity of its voice deserves protection in every corner of our increasingly digital world.